one | two | three | four

1. classical economy

2. neoclassical economy

3. Karl Marx

4. Joseph Schumpeter

5. ordoliberalism

7. critical rationalism

8. philosophical criticism

9. monetarism

This part is only interesting for people who deal with economic problems from an academic point of view. We discuss the topic thoroughly, but we have our doubts about their didactic value.

It is well plausible that the IS-LM model contributed more to the confusion about Keynesian theory than to actually explaining it.

The IS-LM model is the principle responsible for all the existing confusions about Keynesian theory.

The IS-LM model wants to be a representation of Keynesian theory. We never found the original Keynesian theory in textbooks. What we found is the IS-LM model, although this model does not contain the sticking points of Keynesian theory, and is difficult to understand.

The only concept people remember after having studied the IS-LM model is expansive fiscal policy, which is actually an annotation of half a page in the original work.

The lack of demand, a problem to be resolved by expansive fiscal policy, is something that most people believe “intuitively” plausible. For most people it is plausible that a lack of demand leads to unemployment.

This generalised “feeling” about a lack of demand is already described by Jean Baptiste Say, see Say's law.

The refutation of this “feeling” given by Jean Baptiste Say is not very convincing, but in any case he correctly described a widespread feeling.

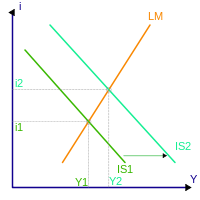

Anyone who has spent at least three semesters studying economics will know the graphic below. It is the famous IS-LM model.

If you Google IS-LM model, you get 35 million results. Unfortunately this only shows that the misleading model is widespread, but it doesn’t mean that the concept is useful or correct.

The model is presented as neoclassical synthesis, in other words a synthesis between Keynesian theory and neoclassical theory. The truth is that it is impossible to make a synthesis of neoclassical theory and Keynesian theory, because they are incompatible with one other.

The author would say that it is pure neoclassical with very little Keynes. To make a synthesis of two incompatible theories is only possible if central concepts of one of these theories are abandoned. That’s what happened in this case.

The IS curve is a presentation of all combinations of interest rate (i) and national income (y) where savings and investment are in equilibrium.

That also means that the market of goods is in equilibrium. What has not been consumed has been saved by some people and invested by others.

This curve can be interpreted in a Keynesian way and in a neoclassical / classical way, and this is the problem. This curve leads to confusion.

In the Keynesian interpretation savings would FOLLOW investments. This would be an interpretation compatible with Keynesian theory.

Investors calculate with a certain profitability of their projects. That means that the cheaper the credit, the more investments there will be. The more investments, the higher the national income. To get to a new equilibrium, national income must increase until savings, which depend on the national income, are as high as the investments. That means that high interest rates lead to a small national income, because high interest rates lead to fewer investments.

[If this is too imprecise for some people, they have to think about the example given above with the “compulsory” savings through taxes or something similar.]

The lower the interest rates, the more investments there will be, the more savings is needed and savings depends on the national income. In this logic savings follows investment and the interest rate is a hurdle to overcome, and not an incentive for saving. (Apart from that 'savings' are not even needed in a situation of unemployment.)

Nevertheless there is a little problem with this curve. The equilibriums described are reached EX POST. They describe different combinations of interest rates and national income levels where investments equal savings, but they don‘t describe how to get from one equilibrium to the other.

[Lets illustrate that with an example. If the saving rate, s, is 0.2 percent and the consumption rate, c 0.8 percent an equilibrium would be

1000 = 800 + 200

Y = c (Y) + s (Y)

If the investments increase by 50 to 250 the national income, Y, must increase by five.

1250 =

1000 + 250]

This is no problem if we only consider the equilibrium as the result of a process, but it becomes a problem if we want to know how to get there.

In textbooks we always find the example of an increase of the aggregate demand through an increase of government spending. That moves the IS curve to the right. But then the question is how the IS curve can be moved to the right without money.

If the government wants to increase public demand, the amount of money must be increased. That‘s the reason why this IS curve, in this interpretation, looks Keynesian, but it is not. Investment is financed with money. Money is not scarce in Keynesian theory, but one must have it.

There is a second error with the IS curve. Savings can only be understood in a real context, in other words as non-consumption, and therefore a reduction of consumer goods in favour of capital goods. But if the IS curve is moved to the right, there is an idle production potential, otherwise the curve can’t be moved to the right. But if there is any productive potential, saving in the sense of the classics is not needed. What is needed is money and that money must be afterwards destroyed when the credit is payed back, otherwise the amount of money would increase indefinitely.

The problem is that saving addresses real relationships. Saving is the opposite of consumption. This is useful, if there is no productive potential left to produce consumer goods. If the only effect of an increase in demand would be an increase in prices, people better save their money.

But in a situation of unemployment, where consumer goods as well as capital goods can be produced, saving is counterproductive. It is only necessary to pay back the credit.

The IS curve mixes two different levels, the level of the real economy and the monetary level, and the result is nonsense.

At the monetary level there is only need for money if we have any idle productive potential. This is not included in the IS curve. What we have is savings, but that’s not what we need.

Understood as a description of equilibriums the curve makes sense. But without money, we can’t move it to the right, as any textbook about macroeconomics will tell you.

The government and nobody can move the IS curve without the amount of money circulation being increased.

Actually the IS curve can only be interpreted in a 'classical' way, which is compatible with the ideas of Adam Smith, David Ricardo or Jean Baptiste Say. This interpretation has nothing to do with Keynes, but in this case there is no mix-up between the real level of the economy and the monetary level. The classics would have put some MONEY to the side, before, because actually only MONEY can be invested. Savings in this sense means not-consumed income of the past, in the form of MONEY. If national income is low, we need high interest rates in order to induce people to save, because foregoing consumption means actually a sacrifice that is only done if the recompensation is high. At the other side demand is strong and investors will therefore be willing to pay high interest rates. If national income is high, only a lower interest rate is neede to induce people to save, but the investors will as well only pay less, because profits are lower.

The classical interpretation would be more coherent in terms of logic, the money to invest would be there, but this interpretation has nothing to do with Keynes. The Keynesian interpretation would be Keynes, but this interpretation doesn’t take into account money and it doesn’t work. To put it short: The IS-LM model is nonsense.

The very name, IS curve, I = investment and S = saving is already misleading, because saving, in the classical sense, is not needed and the main point is missing. The main point of Keynesian theory is how investments are financed and they are financed with money, and money is not scarce.

Savings can only interpreted as a meaningful term at the level of the real economy. Savings is needed if consumption exceeds the productive potential. In this case capital goods, which improve productivity, can only be produced by saving.

The IS-LM model mixes to different levels, the monetary level and the real economy level.

In the IS curve we have no money, and it can therefore only be interpreted in the classical sense.

If savings is the condition for investment, that’s what the classics believe, then the capital for investment purposes is scarce and scarce goods have a price, in this case the interest rate.

In this case only the most profitable investments will be realised, and others, even if they create jobs, will not be realised. The lack of capital for investments can lead to unemployment. The problem is that this scenario excludes the possibility of a right shift of the IS curve. If the government can move the IS curve to the right, there was an idle productive potential, otherwise it wouldn’t have been possible to move it to the right by increasing aggregate demand.

But if the government was able to move it to the right, savings is of no help, but money is urgently needed.

The heart of Keynesian theory is the opposite. The capital for investment purposes is not scarce. For the production of capital, i.e. money, no sacrifice is needed. The heart of Keynesian theory is that the interest rate is not the incentive needed to induce people to create capital and to save.

In a situation of unemployment the interest rate is only a hurdle to overcome with no real function in a market economy.

The heart of Keynesian theory is not only not included in the IS curve, but the IS curve suggests the opposite of Keynesian theory. Investments are financed with money, not with savings.

It is not possible to interpret the model in the sense of Keynes by saying that in Keynesian theory savings depends on national income, because this is irrelevant and is true in both situations.

In the classical version, where part of the income of the past has been saved and in the Keynesian version, were people will save in the future to pay back their credit.

The model doesn’t become more correct by saying that savings depends on income, because that is not the central point. The crucial point is that in Keynesian theory investments depends on money, not on savings.

The LM curve on the other hand shows all the combinations of interest rates and national income, where the money market is in equilibrium, in other words, where the demand for money is equal the supply for money. This means that the return you get by buying a security determines how much money people will keep in their bank account for (almost) no return.

How we define the speculative fund doesn’t matter. Realistically speaking the speculative fund can be seen as the money held in bank accounts for almost no return, or less realistically, as the money people keep under their pillows, with no return at all.

To put it simple: If the return on a security is 15% percent, nobody keeps money in his bank account. If the return is 5%, percent and if everybody expects that the value of securities will fall, people will prefer to keep their money in their bank accounts. It is to assume that the reader of these lines has a strong preference for liquidity, but it is clear that for the reader of these lines as well as for the general public, there is a return where he will withdraw his money from his bank accounts and buy securities, bond, shares etc..

Equilibrium on the money market means in this context, that the interest rates balance the amount of money that people keep in a form that yield no or almost no interest and in a form that is very similar to money, financial assets that can be reconverted to money in any moment, but yields some profit. However for the keynesian theory the distinction is not very relevant, although the LM curve suggest the opposite, because both forms to keep capital have no impact on the real economy, create no jobs and don't increase national income. However the interest rate determined by the money market is the hindrance real investments has to overcome.

If the national income is low, the need for money for transaction purposes is low, because few goods are exchanged. If the amount of money is given, the speculative fund is high.

Money is used for speculative purposes if kept in a way where it yields no, keeping it under the pillow, or very little profit, keep it on the bank account.

In the speculative fund we have a wide range of risk aversion or, as it is called by Keynes, preference for liquidity. This is how Keynes calls it, because liquidity means security. The risk is low if an investment can be reconverted at any moment to the most liquid form, money.

Listed securities are not as secure as money itself, but more secure than real investments, because they can be reconverted at any moment into this most liquid form.

Therefore the speculative fund is held by people who need very high interest rates to be induced to take money out of their bank accounts, where they get no return at all, and to invest it in the stock market.

If the national income is low, the amount of money needed for transaction purposes is low as well, and the speculative fund is high. We can therefore assume that all people with low risk aversion have left the safe haven of liquidity and have invested in the stock market. Quoted share prices are therefore high and the return on these securities low.

(We remember, see above: $5 for a security that costs $100 is not a lot. $5 for a security that costs $50 is a lot.)

If the national income increases some people will have to sell securities in order to get the money for transaction purposes. The quoted share prices will fall, the return will increase. This will induce some people to buy securities who have so far remained in the safe haven of liquidity.

This point is a little bit complicated: We can imagine that some people with a high risk tolerance will sell, because they are obliged to. In isolation this effect will lead to a price decrease for the quoted share. On the other hand less risk-tolerant market players will buy them, and that will raise the share price. But in total the share price will go down and the return will go up.

If the national income increases more and more, a point will be reached were no speculative funds are left. Even the less risk-tolerant will leave the safe haven of liquidity if the potential returns are, say, 30%.

[We can also imagine something different, if we want. If the return for securities is low, only few people will make the effort needed to inform themselves how the stock markets work. But if they can earn a lot of money, they will do it.]

At this point the national income can’t increase anymore if the central bank doesn’t increase the money supply, because there will be no compensation effect if people sell securities once there are no speculative funds left. If in this situation the central bank doesn’t increase the money supply, any increase of national income will increase the interest rates on the MONEY MARKET, which will make it more and more difficult for real investments.

If people can get a return from a liquid security with almost no risk, then the return on a risky real investment must be higher.

The higher the national income, the lower the speculative fund, the lower the share price, the higher the interest rate on the money market, the more difficult it becomes for real investments to compete with the stock market.

Textbooks about macroeconomics distinguish three sections of the LM curve. The liquidity trap, where an increase in national income has no impact on interest rates, the section where an increase in the national income leads two an increase of the interest rates, but an increase in national income is possible and the classical sector, where any further increase of the national income is impossible, because the raise of the interest rates would be so high, that no more investments are possible.

The explanation for the liquidity trap in most textbooks is nonsense. It is argued that more money would tacitly be put in the speculative fund and therefore wouldn’t have any impact on interest rates. This is nonsense. In the liquidity trap it will be impossible to inject more money into the market, because nobody needs it. People will not increase their speculative funds with more money they would have to pay for, if they have no idea what to do with this money. They will simply not accept it.

Institutional investors will not accept more money from the central bank because they already have more money than they need. They will not borrow money from the central bank and pay and interest rates if the only use they have for this money is to put in the speculative fund where they get no return at all. The speculative fund is only interesting for money still in circulation.

What we really see nowadays, we are still in the year 2015, is something different. Institutional investors take the money, but invest it in the stock market, which leads to an increase in stock prices. The interest rate continues to go down, but we don’t see that this has an impact on the real economy.

The point is that institutional investors have to do something with money, because they earn money with money. If they stop taking the money offered to them by the central banks, they go bankrupt.

The sector where an increase of the national income is no longer possible because it would require to sell securities with the effect that real investments would be displaced is called the classical sector in textbooks about macroeconomics.

This logic would be true, if money were capital in the sense of the classics, i.e. if it were not consumed income of the past, if capital were a scarce production factor.

But money is not a productive factor and first and foremost it is not scarce.

In a situation of unemployment we will never see a classical sector in reality. (Unemployment is defined here as idle productive resources.) If there are idle productive resources, the central bank will never keep the money supply low, unless they fear what Keynes calls bottle necks.

If the idle productive resources depend on other scarce resources, there is no way to use them, but in a globalised economy that never happens.

The term classical sector suggests that we have full employment. This is not true for capital, if by capital we mean money, and it is not true for labour. In the classical theory capital can be indeed be a hindrance to full employment, because it is needed to employ workers, see David Ricardo. But it is not scarce, if it is just money, it can't be a hindrance for full employment.

Capital in the sense of money is never scarce, and the LM curve doesn’t allow for any conclusions about labour. Even in the classical sector unemployment on the labour market is possible.

It is true that in a classical situation of full employment more money would only lead to inflation and inflation to higher interest rates, because lenders will anticipate inflation, but the idea that we get to a classic situation by keeping the amount of money scarce is not only misleading, but it is contrary to the conclusions to be drawn from Keynesian theory.

If we accept this interpretation, the central banks can reach this classic situation at any level. They can keep money as scarce as they want.

What Keynes actually said is that the amount of money must be increased until we get to full employment. The interest rate has to be lowered until there are sufficient investments to get to full employment. Beyond full employment, lowering interest rates is useless, because we would reach a situation where an increase in investment would only lead to inflation.

The LM curve could be interpreted in a different way, that is as well compatible with the keynesian theory: The money market dominates the goods market and the goods market dominates the labour market. We get to the same conclusion without a speculative fund.

The argument starts at the same point as before with speculative funds. To put it otherwise: It doesn't make any difference if the money is money is kept in absolute liquidity or in relative liquidity. The point is, that it is not used in an economically usefull way. The distinction made by the LM curve between absolute liquidity and relative liquidity complicates the understanding of the central argument.

If national income is low, there is only little need for money for transaction purposes. There is therefore a lot of “surplus” money that wants to be invested somewhere. There is therefore a big supply of money, and for money the same thing is true as for potatoes. If supply exceeds demand, the price, in the case of money the interest rate, is low. No matter whether it is invested in real investments or in the stock market, it can only be invested at a small return.

The economy will reach a point where there is no money left for investment purposes. Beyond this point any attempt to increase the national income will only lead to an increase of the interest rate with the result that new investments can only be realised at the expense of other investments. We have reached a “classic” situation, if the central bank keeps money scarce, where money is a production factor.

If we want to put it in more real economic terms: Money becomes scarce in this situation if the more profitable investment can really replace the less profitable one. (If money is kept scarce by the central banks.)

The problem with that interpretation would be that the “surplus” of money would in any case have an impact on demand. If people invest it in the stock market, the type of interest would decrease and that would have an impact on real investments. If it is invested directly in a real investment, it would have a direct impact on demand.

We would still have a competition between real investments and purely speculative investments, but there would be some kind of investments. In the keynesian theory exists as well the possibility that all the money is hoarded.

If we stick to the original Keynesian theory, a situation is possible where the “surplus” of money doesn’t have any impact. If stock prices are very high, the return would therefore be very low, and so people will keep their money in the speculative fund. They do that firstly because the return is too low to induce them to leave the safe haven of securities, and secondly because they fear that the prices for shares and similar financial assets will decrease and they will lose money.

In this case people will keep their money in a way which yields them no return at all, but where is at least safe.

The difference between these two interpretations is, with or without a speculative fund, that in the first case it can be explained that money has no impact at all on the economy. In the second case there is always an impact, directly or indirectly.

That doesn’t change the central message of Keynes. That central message is that the interest rate which is determined in an arbitrary way on the money market, which actually is something like a casino, that this interest rate determines the hurdle real investments have to overcome.

To put it more clearly: The labour market depends on a casino.

The Keynesian version, with its concept of speculative funds, explains why people keep money in their current accounts where they get (almost) no return.

[We find it important to mention that the term insecurity, the reason for the liquidity preference, could be stated more precisely. Insecurity is a problem of a lack of information that doesn’t allow potential investors to find out about profitable real investments. For the sake of simplicity Keynes explicitly excluded these kinds of problems from his analysis. In the opinion of this author this is a problem that should be addressed.]

As far as institutional investors are concerned speculative funds are less important. They will not increase their speculative fund by borrowing money from the central banks. They will not pay for money, if they don’t get a return from this money.

The main thesis remains unchanged: The money market dominates the goods markets.

What we see at the moment, we are still in 2015, is that institutional investors take any amount of money offered to them by the central banks to speculate in the stock markets. The return on these papers, the dividends which determine their interior value is decreasing. Institutional investors speculate on the stock price. The speculation is on the value of the securities, not on the dividend. The interest rate for which the banks lend money will not decrease.

For institutional investors and similar institutions such as hedge funds the casino is more interesting than the real economy. This is always true.

We are not going to discuss monetarism here. Monetarism argues with the same monetary transmission mechanism as Keynes, but it assumes that an increase in the money supply will lead to inflation. The reader can try to find out himself what would happen then. For further information about monetarism the reader is referred to the chapter about Monetarism.

Monetarism can’t undermine the basic claim of Keynesianism. Monetarism assumes that an increase in public demand will lead to inflation. Inflation would lead to a higher demand for money for transaction purposes. This will lead to a raise in interest rates.

The problem is that we have not had any inflation for 30 years, and it is very improbable in a globalised economy that inflation can be induced by an increase of demand, because in a global economy almost any demand can be satisfied with the existing productive potential. Inflation can only occur if it is driven by the cost side, for instance by rising prices for raw materials.

The problem is not inflation, the problem is the indebtedness of the states, as pointed out in chapter III.

In any textbook about macroeconomics anywhere in the world Keynesian theory is taught on the basis of the IS-LM model. It is asserted that this model is a correct interpretation of Keynesian theory or a neoclassical synthesis. This can be questioned. With some effort we can interpret the IS-LM model in a Keynesian way, but the original text is easier to understand.

We expect from models that they simplify reality maintaining the relevant aspects of a certain problem. A roadmap will not show how much the people earn who live in a certain area. This is irrelevant for a driver, but a road map will show the roads.

But if it is easier to observe reality directly than through a model, the model is not needed.

The model suggests a relationship between savings and investment on the one hand, and the money market on the other, whereby the causal relationships are unclear.

If the IS curve is moved to the right through an increase in public spending, one of the typical scenarios discussed in textbooks, national income increases and interest rates, at least in the sectors outside the liquidity trap, will increase.

The same could be achieved by increasing the money supply, which moves the LM curve to the right. That’s the other typical case we find in any textbook. In this case national income would increase because the interest rates decrease.

If the interest rate is lowered, the LM curve crosses the IS curve at a lower interest rate and national income is higher.

However the IS-LM model describes the casual relationships in a wrong way, which makes it difficult to understand this model.

If government spending should be increased, in other words, if the IS curve should be moved to the right, it is not savings that is needed, as the IS curve suggests, but money.

The IS-LM Model suggests that there are two different options to increase national income and to increase employment: Expansive fiscal policy and/or expansive monetary policy.

That is nonsense. In both cases more money is required, but not capital. An increase in the aggregate demand through an increase in public spending is only possible if the idle money in the speculative fund is transferred to the government or if it is transferred to real investments that are so profitable that they beat the returns from the stock market.

The LM curve suggests that money can be injected by the central banks alone. That is not possible either. The central banks can only inject money if someone wants to have it.

Sentences like “if the government increases the aggregate demand now, the IS curve will shift to the right” are nonsense, although we find them in any textbook.

Without money the IS curve doesn’t shift at all.

[Insertion: Why do macroeconomics textbooks say the IS curve shifts to the right if there is an increase in public demand? To understand that it is necessary to remember how the course of the IS curve is explained: The interest rate, for which money can be borrowed is fixed. If it is high, there are only small investments, because only very few investments are able to overcome this hurdle. The national income needed to provide the necessary savings, and savings depends on income, is therefore low as well. The lower the interest rates, the higher the investments, the higher the national income necessary to generate the corresponding savings.

But if the government increases public demand, we don’t have a movement ALONG the IS curve. We have more investment at the same interest rate. The curve moves to the right, at least in theory. In practise it doesn’t work. If it wants to invest, the government needs money. That saving increases until the amount of savings equals the amount of investment, the explanation above, might be true, but that is not the interesting point. The interesting point is that the money needed to finance fiscal policy must be eliminated afterwards. In other words: SAVINGS, income not used for consumptions, happens AFTERWARDS. But the money, the government must have BEFORE.

In a similar way we can deduce the right shift of the LM curve: If the amount of money is high, the speculative fund is high. The market participants who are most prepared to take risks will have bought listed securities. Share prices are therefore high, the return low. If national income increases, some of these high-risk investors will be obliged to sell their securities in order to get money for transaction purposes. This will induce some owners of the idle speculative fund to invest in listed securities, which will partly compensate the effect, but on average the holders of securities will be less willing to take risks, and therefore the return must increase in order to induce them to leave the safe haven of liquidity. This goes on until there is no speculative fund left.

If the the central bank increases the supply for money, the LM curve moves to the right, because the speculative fund increases.

The problem is that sentences like “if the central bank increases the money supply the LM curve moves to the right” are nonsense. The central bank can offer money, but it depends on the demand for money whether this money is actually bought, not on the supply.

No farmer can decide autonomously how many potatoes he wants to sell, and neither can the central bank decide autonomously how much money it wants to supply. Institutional investors will not accept the money offered to them just to increase their speculative fund.

That doesn’t change anything in Keynesian theory, but the IS-LM model is nonsense.

It is still true that institutional investors, especially banks, will accept the money, even if they only use it to speculate on the stock markets.

The interest rate is low right now, we are still in 2015, near to zero in fact, but the spark doesn’t leap to the real economy where the jobs are created. The money market dominates the goods markets, this is the main message of Keynesian theory, and that is what we see right now.

The European Central Bank injects more and more money into the market, but that has only driven up stock prices and has had no impact on the economy.]

The real problem is obscured by the IS-LM model. The lack of demand is only an effect of the preference for liquidity, but not the cause. The problem to be resolved through an expansive fiscal policy or through an expansive monetary policy is the same in both cases. The problem to be resolved in both cases is the same.

The real difference is this: In the case of expansive fiscal policy the government redirects idle money to a productive use, and in the case of expansive monetary policy the interest rate determined by the money market is too high and must be lowered.

In both cases “saving”, actually the destruction of money, follows investments.

The lack of demand is only an effect of the preference for liquidity, but not the cause of the problem.

The difference between expansive fiscal policy and expansive monetary policy is a different one. The government can invest directly in case of a total preference for liquidity. The risks of this policy have been described in III.2. But money, not savings, is needed to do that.

With ex-ante saving, as suggested by the IS curve, the IS curve can’t be moved to the right.

The IS curve describes situations where the goods market is in equilibrium, in other words, where savings equals investments, but it does not explain how to get from one equilibrium to another.

This has as well the consequence that the crowding out effect discussed in textbooks about macroeconomics doesn't exist. It is assumed that by increasing the aggregate demand, a righ shift of the IS curve, the interest rates increases and other investments will be kicked off. That is not going to happen, because a right shift of the IS curve will either reduce the speculation fund or increase the amount of money. There will be no crowding out effect, at least not by the transfer mechanism suggested by the IS-LM model.

Classical theory assumes that finding real investments is no problem, and that the main problem is a lack of capital. Keynesian theory, more realistically, assumes that finding profitable real investment is the problem, and capital is no problem at all.

There are two different ways, in Keynesian theory, to resolve that problem: by lowering the interest rate, that way lowering the hurdle real investment has to overcome. Another option is direct government investment, if the liquidity preference is so high that even an interest rate of zero wouldn’t induce enough investment to reach full employment.

It is often said that expansive fiscal policy will trigger inflation due to bottlenecks. This author would say, that this would happen anyway. If the economy grows, for whatever reason, some resources will become scarce and in order that more of them are produced, prices have to increase. From this point keynesian policy is just an accelerator of what would had happen anyway.

(However the discussion is somehow theoretical, because in a globalised economy there is no such a thing as scarce resources, at least inside realistic margins.)

To summarise: The IS-LM model is something between confusing and wrong, a strange mix between the monetary level and the real level. It induces a mechanical thinking that has nothing to do with reality, a way of thinking considered fatal by Keynes.

People move the IS and LM curves from the left to the right and from the right to the left without understanding what they are doing and afterwards they wonder why reality is not as simple as it seems to be on paper.

We don’t need models which obscure reality instead of clarifying it and which are irrelevant for explaining reality. It would be better to eliminate the IS-LM model from the textbooks completely.